International Research Training Group

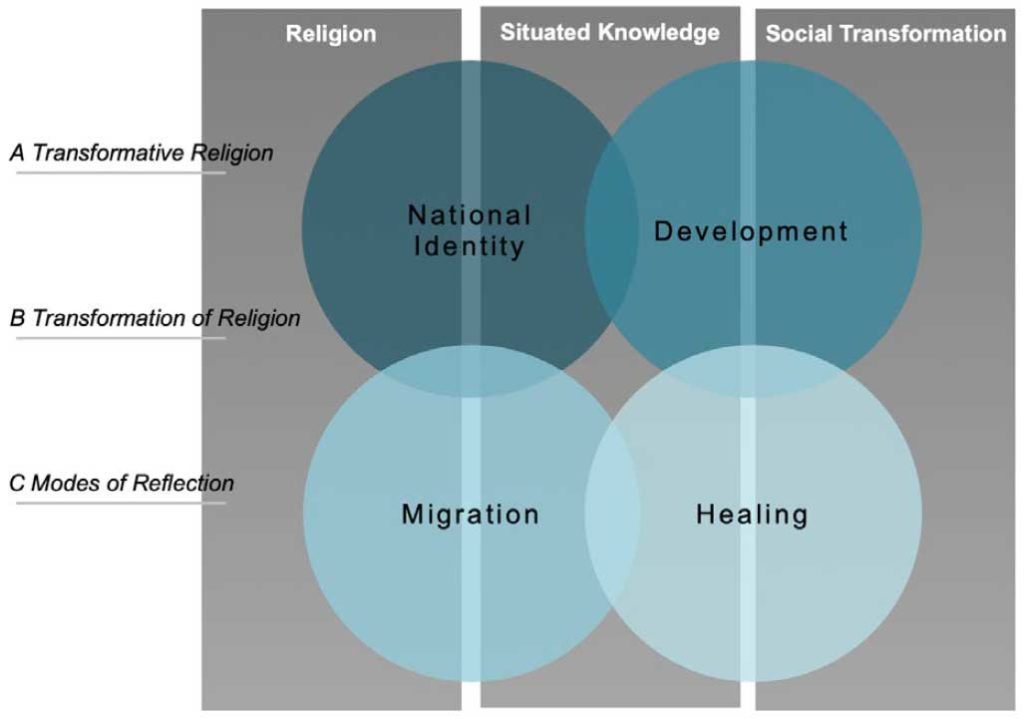

Transformative Religion Religion as Situated Knowledge in Processes of Social Transformation

Events

Yoruba Pentecostalism and Child Witchcraft

Accusations: Migration, Authority, and

Safeguarding (Nigeria and the UK)

- 9th February 2026

Based on research on Yoruba (Nigerian) Pentecostalism in Nigeria and the UK, this lecture explores why accusations of child witchcraft persist and how they circulate across national borders.

The lecture examines the role of religious authority, gendered power relations, and migration in shaping the credibility of such accusations and the practice of deliverance. It highlights how spiritual interpretations of misfortune can become entangled with family tensions and economic pressures, sometimes escalating into forms of faith-based child abuse.

In conclusion, the lecture reflects on questions of collective responsibility and outlines practical, culturally sensitive, and legally informed pathways for safeguarding that are applicable to churches, communities, and professionals working in diverse contexts.

About

As of January 2022, the new German–South African International Research Training Group (IRTG) „Transformative Religion: Religion as situated knowledge in processes of social transformation“ will take up its work. Funded jointly by the South African National Research Foundation (NRF) and the German Research Community (DFG) with a gross total of roughly € 4,9 million (ZAR 82 million), the project transdisciplinarily investigates the impact of religion in processes of social transformation and the impact of these transformations on religion in contemporary global societies with an intercontinental perspective. It seeks to contribute to recent academic research and public debates on the complex relationship between religion and society.

This project is the second IRTG in the history of German-South African academic cooperation, currently the only German IRTG in cooperation with an African country and the first one to focus on issues of religion. For the next five years, the IRTG will present the opportunity for extended transcisciplinary research training to up to 54 doctoral candidates under the guidance of more than twenty interdisciplinary principal and associate researchers from a variety of academic disciplines in the cooperation of four academic institutions: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (FRG), Stellenbosch University, University of the Western Cape and Inyuvesi YakwaZulu-Natali (UKZN)(all RSA).

Against the backdrop of discursive differences in perceiving and positioning religion in the field of knowledge between the global North and the global South and with a distinctive decolonial approach, this IRTG aims at a critical epistemology through which the situatedness of religious knowledge production and reception in processes of social transformation can be researched. In case studies from contexts in the global South and North, the IRTG seeks to investigate religion as specifically situated knowledge functioning as a resource and as a site of social transformation. It engages scholars from two continents and a variety of disciplines to go beyond conventional research approaches.

Research Area 1: National Identity

Becker, Lecocq, Meireis, Punt

The first research area will focus on the problem of the relationship between normative elements of situated religious knowledge in processes of public deliberation and conflicts of hegemony and power concerning modern nation states and their corresponding social imaginaries. The comparison between Western European and African contexts will help elucidate the dynamics of this relationship on a global scale. Research will rely on the one hand on concepts of the imaginary and the nation as imagined community, as well as concepts like political theology, civil religion or public theology. It will, however, also take into account that some of these concepts are contested on the grounds of their apparent power asymmetry and eurocentrism and also that the interrelation of national identities and so-called ‘local’ or ‘traditional’ religions is mediated by the experience of colonisation with its consequences for colonisers and colonised alike.

It is however vital to distinguish between national identity and feeling on the one hand, and national political organisation on the other, while appreciating and analysing the variety of relationships that have existed between the two. Furthermore, in line with the affective turn, exclusive national identities (‘nationalism’) must be regarded not merely or even mainly as a realist exercise in political power-seeking, but as a process intimately bound with morally constituted concerns about the nature of society and how to live a good life. Recent examples include the South African discourse portraying the country as a ‘rainbow nation’, which essentially is a religious notion; the instrumentalisation of religion in the framework of a nation part of the ‘Christian Occident’ as in contemporary European public discourses on migration; and the open and often violent contestation of the secular nature of the state and the nation by popular and mass-supported religious movements in a number of African countries.

Depending on the way in which dynamic religious practices, concepts and narratives are interwoven with the ever-changing constitutive social imaginaries of the nation state, i.e. national identity, the concept of religion as situated knowledge is crucial for understanding the construction of such collective identities past and present, as well as their political impact and the way in which religion becomes socially transformative but also undergoes change in the process. And of course, the opposite holds true: research into the ongoing development of national identities, nation states and neo-nationalism is a field of utmost social relevancy where the impact of religion as situated knowledge and the way religious practices, semantics and concepts change in the course of that impact may be studied in depth. Thus, national identity has been and remains deeply entangled with religious notions, practices and ideas bearing a socially transformative impact on a collective and individual level. Historically, two phenomena may be discerned: nationalisation of religion and sacralisation of the nation. Nationalisation of religion refers to an adaptation process during which the religious agents accept the value system of nation into their religious beliefs. Sacralisation of the nation implies a transfer of traits, functions and characteristics usually attributed to religion to the nation, resulting in a structural analogy between conceptions of nation and a given concept of religion. Yet within a single nation, even closely related religious ideas, concepts, narratives and practices may play out in quite different ways and can be readily understood as features of a situated knowledge orienting and articulating moral or political attitudes. Both these processes – nationalisation of religion and sacralisation of the nation – can be considered situated knowledge that shapes social transformation. In African as well as in European contexts, national identity construction undergoes a process of change. In Europe and Germany, strong and exclusive national identities and nationalisms seem to be back on the agenda. An intensive renationalisation of policies and polities is visible, implying a retraction of democratic mechanisms for governing international relations, while especially right-wing groups focus on migration to justify such policies. This phenomenon has been labelled ‘neo-nationalism’ and differs considerably from the 19th and 20th-century ‘paleo-nationalism’ aggressively aimed at nationbuilding; rather, the former has emerged as a defensive retraction into the seemingly secure borders of the nation state. Even when these countries’ respective political figures don’t appear overly religious, religion is often heavily implicated in their discourse on national issues and has recently played out in novel forms of religiously engrained neo-nationalism.

In Africa, national identity is intimately tied to colonial history in its different eras. In present-day South Africa, for instance, white identity claims in different forms – Dutch and British colonialism, white ‘Boer’ supremacism and the apartheid regime – fed into a nationalist ideology in the Afrikaner narrative, carrying deep religious undercurrents which return in what may be labelled ‘enclave nationalism’. In (Southern) Africa, the debate about national identity concerns the nature and role of postcolonial and decolonial epistemes, informed by scholarship from other parts of the world. The long-suppressed black nationalist awakenings as seen in movements such as Black Consciousness, and later in the democratic change connected to the African National Congress and protagonists like Nelson Mandela, Desmond Tutu or Alan Boesak, invoked a different form of national identity and narrative, often referred to as ‘Rainbowism’. Though currently deteriorating, these national(ist) impulses have also been articulated in religious terms.

The concept of religion as situated knowledge is crucial for understanding the construction of collective identities past and present, as well as their political impact and the way in which religion becomes socially transformative but also undergoes change in the process.

Research projects within this first area will look into religious undercurrents and practices of such divergent tendencies in national identity formation by looking at the role of religious practices and semantics in political statements proper, the religious dimension of national affiliations and disaffiliations in migrant communities, or the contribution of different hybrid religious practices and narratives in the complex processes of collective identity construction between national, regional, tribal or religious group affiliations in the face of constant social change, extending not only to economic concepts like development, but also to practices of healing.

Research Area 2: Development

Bowers du Toit, Gräb, Kumalo, Okyere-Manu, Swart

The second research area will explore the transformative role of religion in development discourses and practices. Over the last two decades a growing interest in ‘religion and development’ has emerged among scholars, policymakers and development practitioners in the Global North and South. It is an interest that is not merely confined to Christianity but increasingly explores the contribution of the other traditions to the religion and development debate, especially noticeably Islam. At the same time, the evolving field of religion and development is highly transdisciplinary and includes scholarship from a range of social science disciplines as well as from religious and theological studies. Policymakers, development agencies and international organisations have recognised that religion is a highly relevant factor for or against development and substantially contributes to knowledge production in the field.

However, in the West or Global North the discussion is taking place within a secular framework following an instrumental understanding of religion. It asks for the potential contribution of religious communities (discursively secularised as ‘faith-based agencies’) as part of a secular development agenda. This stands in contrast to an agency-based perspective of religious communities, for whom professional and academic experts’ notions of development represent only one dimension in more comprehensive human and social transformation initiated and conceptualised by religious actors themselves.

That critique also challenges the framework of ‘development’ proper and implies a fundamental critique of dominant Western notions of (sustainable) development. Researchers and policymakers are only beginning to realise the implications of this critical insight for development theory and practice. This critique also resonates with concurring voices promoting alternative concepts like human flourishing, buen vivir or ecological swaraj. It stands in stark contrast to concepts of development cooperation developed in the Muslim world since the 1980s, in which material development and religious development (usually framed under da’awa or mission) are directly intertwined.

The concept of development has been severely criticised from the angles of postcolonial studies and the post-development debate. Moreover, scholars from Africa have highlighted that in the UN development discourse ‘development’ is still a Western-centred and secular-framed concept of social transformation that has to be recentred regarding a development agenda initiated by local (religious) communities and formulated in coherence with African cultures, cosmologies and world views.

References to African situated knowledge about the conditions and goals of development not only imply a fundamental critique of dominant Western notions of (sustainable) development, they also shed light on a completely new role of religious communities in the African context. Particularly in African contexts, religion should be regarded not only in an instrumental sense but as a decisive factor in processes of social transformation, as religious conceptualisations are among the crucial elements informing the situated knowledge of the needs people formulate, and as religious structures enhance their capacities to act self-determinedly. Simultaneously, religious knowledge and practices form a decisive, if ambiguous, element in the structuration of political power and elite decision-making processes informing and shaping development policies. Without neglecting the problematic impact of religious fundamentalisms in political and societal conflicts, it is time to uncover the productive role of local religious communities as agents not only of development but also as producers of a decolonising development agenda. They realise development agendas ‘from below’ and contribute to its realisation due to a situated knowledge about the conditions and goals of development.

The research area will analyse the meaning and implications of local situated discourses and practices focused on a decolonised concept of development. Particular attention will therefore on the one hand be given to religiously shaped notions of development in various forms of Islamic south–south development cooperation between African states and the Gulf countries as well as African states among themselves, especially Morocco, Libya (prior to 2011) and Algeria, such as Islamic finance. On the other hand, the focus will be on postcolonial religious movements, such as African Independent and African Pentecostal Churches. Their world view, in which the spirit world is real and not strictly separated from the social and material world.

The religious factor, in the approach of this research area, is seen not only functionally as a resource for development activities but also as a force to transform the conditions, instruments and goals of development. The research area seeks to investigate how local religious communities become agents of sustainable development more than in an instrumental sense, but by reformulating the very notion of sustainable development using the situated knowledge of African cultures and world views. It intends to relate the quest for ‘situated knowledge’ in processes of social transformation in an interconnected way to particular religious practices, actors and discourses. It is looking for conceptual strategies of decolonising development and in particular how they are inspired by development discourses situated in African cultural contexts. In accordance with the transdisciplinary nature of the wider research field, the approach pursued in this research area is highly transdisciplinary. The doctoral projects will incorporate into the research process the perspectives, expertise and knowledge produced

by scholarship across the transdisciplinary field of religion and development but also by policymakers and practitioners and representatives of religious communities from the beginning.

Research Area 3: Migration

Feldtkeller, Foroutan, Forte, Römhild, Settler, Simon

The third research area starts from the assumption that migration is as essential for the constitution and transformation of religion as religion is for the context of migration, i.e. the societies involved in these processes. In this way, this research area can be considered a central field in which to study both the transformative impact of religion and how it is transformed. However, the deep and influential entanglement of religion and migration is acknowledged in different ways, and can be understood in terms of three trajectories: (a) religious narratives of migration such as narratives of the promised land in the Abrahamic traditions, the Hijra of the prophet Mohammed in Islam, and pilgrimage in African religion; (b) religious responses to migration through narratives of rights, and regimes of care and hospitality; and finally, (c) how religion is deployed within the context of migration, whether to generate meaning, cope with anxiety, harness resilience, or build networks of belonging, information and exchange.

At present, and significantly as a result of migration, societies are experiencing an unprecedented pluralisation of religion and a simultaneity of religious traditions and new religious formations. As a result of migration and mobility and of the transit of concepts, discourses and practices through media and other means of communication, local religions increasingly (re)constitute and transform themselves in relation to other local and global knowledge formations. Therefore, the study of social transformation at the intersection of migration and religion can greatly benefit from the transdisciplinary and the transcontinental scope of perspectives and experience assembled in the proposed IRTG. By way of mobility and migration, not only the believers are mobilised, but their religious ideas and practices, both geographically and culturally, are moved, transformed and hybridised as well. In essence, religious practices always refer to different origins and genealogies, and because they tend to coexist with other such practices in the same location, they challenge local capacities to tolerate ambiguity. Furthermore, entire transnational religious spaces are constituted by religious concepts and discourses, practices and materialities circulating among different global networks of diasporas. Through the modes and techniques of advanced mediatisation, diverse religious knowledge is dispersed globally and resituated in the respective locations where it is appropriated for use in everyday life.

Religions are constituted not only by physical and mental movements like pilgrimage or the quest for meaning, but also, historically, by violent expeditions of conquest and crusade and, presently, by religiously motivated violence but also by anti-migrant nationalist and racist appropriations of religious identifications and by anti-religious ascriptions of a threatening cultural otherness resulting in processes of bordering and the exclusion of migrants. While focusing on the present, our approach to religion and migration cannot be uncoupled from the various historical forms of political instrumentalisation of religion, especially in nationalist and colonial histories of violence, exclusion and imperialisms. It pays special attention to the ways in which such histories re-emerge at the expense of the opportunities afforded by migration. Today, the Mediterranean border zones of the EU reach out deep into the African continent – a border regime meant to keep people from migrating towards Europe. And also between African states mobilities are increasingly interrupted by enforced borders. Thus, all over the Afro-European space migrants and refugees are subject to fierce processes of exclusion, deportation, illegalisation and precarisation – often combined with harassment because of their religious orientations. But exactly under such hostile and even lethal conditions, religious knowledge is mobilised in diaspora communities as a means of helping to navigate across borders and boundaries, as a means of self-empowerment, and as a resource of social networking and support. This research area will explore how religious knowledges are situated in such long-term histories of migrating and navigating across borders, and how they are shaped in and appropriated to today’s postcolonial conditions of mobility.

In the South African context, the transformation of post-apartheid society is reflected upon and debated against the background of intra- and transcontinental migration and the great impact of diverse religious knowledges, ranging from ‘precolonial’ traditions to new postcolonial Christian churches, Pentecostalism and Islam. While, traditionally, migration studies concerned with Africa have focused on either African diasporas or forced migration within the continent, transdisciplinary research on the interactions of migration, religion and social transformation has turned its attention towards persisting and changing ethnic-racial factors and religious knowledge in the quests of Indian Muslims, Somali Muslims and other African migrants for acceptance, inclusion and recognition by different religious groups in colonial, apartheid or post-apartheid contexts.

In Germany and Europe, however, the impact of other-than-Christian religious ideas and practices has received the most attention, if at all, in the fields of religious studies and migration research. In line with the secularised notion of European society, religion has been relegated to the domain of the cultural ‘other’. This focus on the ‘religious other’ has hampered an adequate perception and acknowledgement of the ongoing and even increasing role of religion in processes of social transformation not only within migrant and diaspora communities, but also in the European societies in general. Three tendencies can be detected and studied with regard to our research questions: 1) the role of reappropriated, often ‘pagan’ religious knowledge in nationalist and racist movements all over Europe, but very significantly in the post-socialist South-eastern Europe; 2) the rather opposite adaptation of non-European, non- or neo-Christian, also ‘pagan’ religious knowledges in critical social movements concerned with the ecological risks and the social disintegration and de-solidarisation brought about by the rise of the colonial and secular modern; 3) the widespread inclusion of religious knowledge and practice in European mainstream everyday lives, for example the spread of yoga, meditation and new forms of urban religious practices.

The third research area within the IRTG will therefore focus on studying the impact of moving and dynamic religious ideas and practices on social transformation from a much broader perspective. The focus will be on how religious knowledge moves across boundaries and borders, how it mobilises the social imagination of people in local contexts and on the move, and how it becomes transformed in these processes. This will challenge the dominant European discourse concentrating on Islam and the migrant other, both by broadening the view within Europe and by drawing from the African research context. The research area will especially focus on transnational and transcontinental European–(South) African entanglements of religious and migratory practice that are widely neglected in the current scientific and political debates. It will thus allow for a rich exploration which reconsiders the impact of religion as situated knowledge in the realm of cross-border mobilities in and between transforming societies.

Research Area 4 Healing

Klaasen, Kluge, Mbaya, Naidu

The fourth research area focuses on the question of how local healing practices, determining and being determined by religious habits and practices, are impacting social transformation processes. One of the prominent foci within this IRTG field is on religiously motivated healing practices in relation to mental suffering, as well as how mental health and suffering are constructed outside of the biomedical discourse. It thereby relates to the increasing literature on religion and mental health and psychosocial support, particularly in contexts of rapid social change and conflict and migration. The ‘healing’ research area offers the opportunity to examine how everyday (healing) practices, in their historically and socially developed localities, impact on social transformation processes in global societies and are simultaneously impacted by these processes.

European healing traditions have evolved over the past few decades with an ever-increasing focus on evidence-based biomedicine, while other healing concepts continue to be conceived primarily as complementary or alternative. The distinction is seemingly based on a duality of care, in the sense that medical science is dedicated to the concerns of the body while pastoral counsel is dedicated to spiritual concerns and care for the soul. However, this situation differs in some ways from that of South Africa, for example, where we find cultural examples of a more holistic understanding of healing, outside of normative discourses. For example, health, illness and healing are constructed differently within traditional African ontological understandings and world views, which do not suffer from a Cartesian bifurcation or mind–body dichotomy. In traditional African culture or even within contexts of African Indigenous Churches, health and healing are facilitated by the ‘isangoma’, who mediates between the realm of the living and the realm of the ancestors, which are seen to coexist simultaneously. While relegated as ‘culture-bound’ illnesses by early anthropologists, insights into African culturally constructed understandings of health and healing can contribute to situated understandings that offer meaningful healing practices to individuals, while also contributing to the overall psychosocial well-being at the community level. In turn, there is also potential to grow the scholarship on healing practices in the African context, and in the context of African Traditional Religions which include the ancestors and rituals as core elements. Here, religion is constitutive for the understanding of healing, of which faith and rituals are indispensable components.

Although the WHO has begun integrating the world’s diverse healing practices into their concepts, programmes and policies in recent years, it can be observed that religiously and spiritually shaped explanatory models of suffering and associated healing practices remain marginalised. Reviewing WHO reports, it becomes clear that such practices are primarily conceived as peculiar to the Global South – as the ‘Other’ – and thus as an ‘addition’ to the norm. This would appear to contradict the WHO’s ostensibly holistic definition of health: ‘A state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not just the absence of disease or infirmity.’ Here, health is defined as a result (i.e. a state). Healing, on the other hand, in the proposed IRTG is conceived as an option, a process, involving the subjectivity of those affected, and comprising not only physiological processes but also psychological, emotional, social, spiritual and religious ones. This allows for the opening of discourses and interpretations in the field around the tension between supposedly objective science and religious understandings by laypersons and experts, including those of ‘healer’, ‘healing ministries’ or Jesus as model.

At the same time, it presents us with a particular challenge in that, in Euro-American medical discourse, neither an operationalised definition nor an explanation for the mechanisms Proposal of healing exists outside of those referring to physiological processes. Interestingly, a study conducted through interviews with medical experts on the concept of healing has resulted in positing three main associated themes of healing: holistic, narrative and spiritual. Furthermore, it described healing as an intense personal, subjective experience-related process of restoration of meaning in the context of individual distressing experiences. As such, the aim of healing becomes the transcendence of suffering and not merely the absence of illness.

One exemplary context for studying the interactions between locally and translocally informed concepts of healing is the Pentecostal context. Especially Pentecostalism, the dominant and in-itself enormously diverse form of Christianity in contemporary Africa, understands itself as a ‘religion of healing’. Here we can find differentiated relations between local and traditional healing practices, Christian concepts and practices (prayer, blessing, exorcism), and medical science. This is especially true of Pentecostal communities which synthesise global trends, media platforms and networks on the one hand with local practices, traditions etc. on the other. In these groups, healing can also be interpreted as a kind of initiation ritual and signifier for belonging; a conception which is often hard to reconcile with the specifically European/North American concept of psychiatry. Unable to open up to regular clergy about their sickness – often related to mental issues – adherents often resort to traditional healers and are thus ‘forced to live schizophrenically in two different worlds’.

Against this background, the ‘healing’ research area is theoretically and methodologically oriented in the research traditions of cultural psychology, transcultural psychiatry, psychology of religion, religious studies, social and cultural anthropology, critical medical anthropology, ethno-psychiatry, ethno-psychoanalysis and practical theology, especially pastoral care and pastoral counselling. The aim is to investigate locally varying interpretations of illness and healing as well as related local, national and global power structures in a qualitatively and quantitatively empirical, medical anthropological research approach, which views the actions and concepts of individuals and larger social units in relation to these basic themes of embedded human experiences. Research projects within this area will explore the entanglements between healing concepts and processes, migration of people, materials and knowledge, nation-building, ‘morality’ and religion in the contemporary world, focusing on Germany/Europe and South Africa. The main question is, what role does religion play in these processes of social transformation in the local healing contexts? We will explore the translocal interactions between psychiatric-medical and so-called traditional and spiritual theories and practices in dealing with mental suffering. The focus here is on the interactions between sociocultural, historical (local) ideas and translocal influences resulting from (re-)migration movements and the establishment (import) of healing practices in those global contexts. One challenge will be to describe modes of coexistence and inhibitions of different explanation models, symbol systems and assumed mechanisms of action in local contexts, and their conditionality due to locally occurring social transformation processes determined by religious practices. In addition, we intend to draw conclusions about complementarity, competition, overlap and the resulting consequences for those affected and professionals in everyday practices.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.